By Karen Shih, May 24, 2024, Maryland Today.

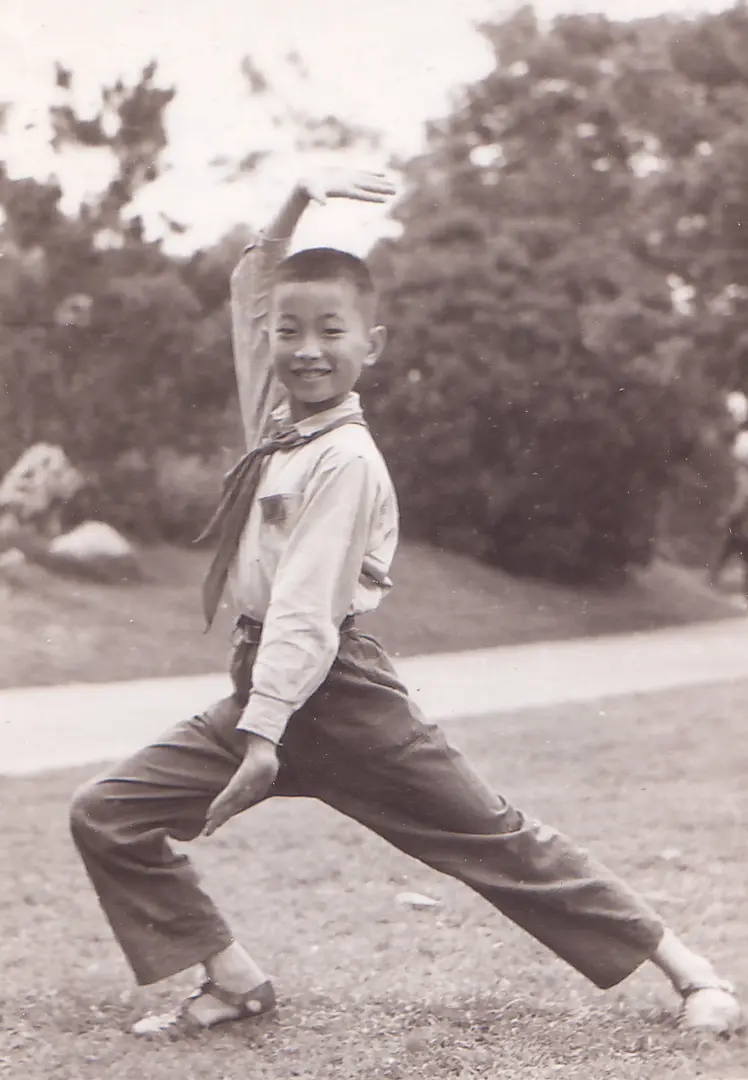

As a teenager in China during the Cultural Revolution, Ming Wang Ph.D. ’86 faced a bleak future. The government had shut down all colleges and universities. Twenty million youths like him were being sent to rural labor camps. To try to save him from that fate, his parents pushed him to learn Chinese dance and musical instruments, hoping he could instead join a government dance troupe.

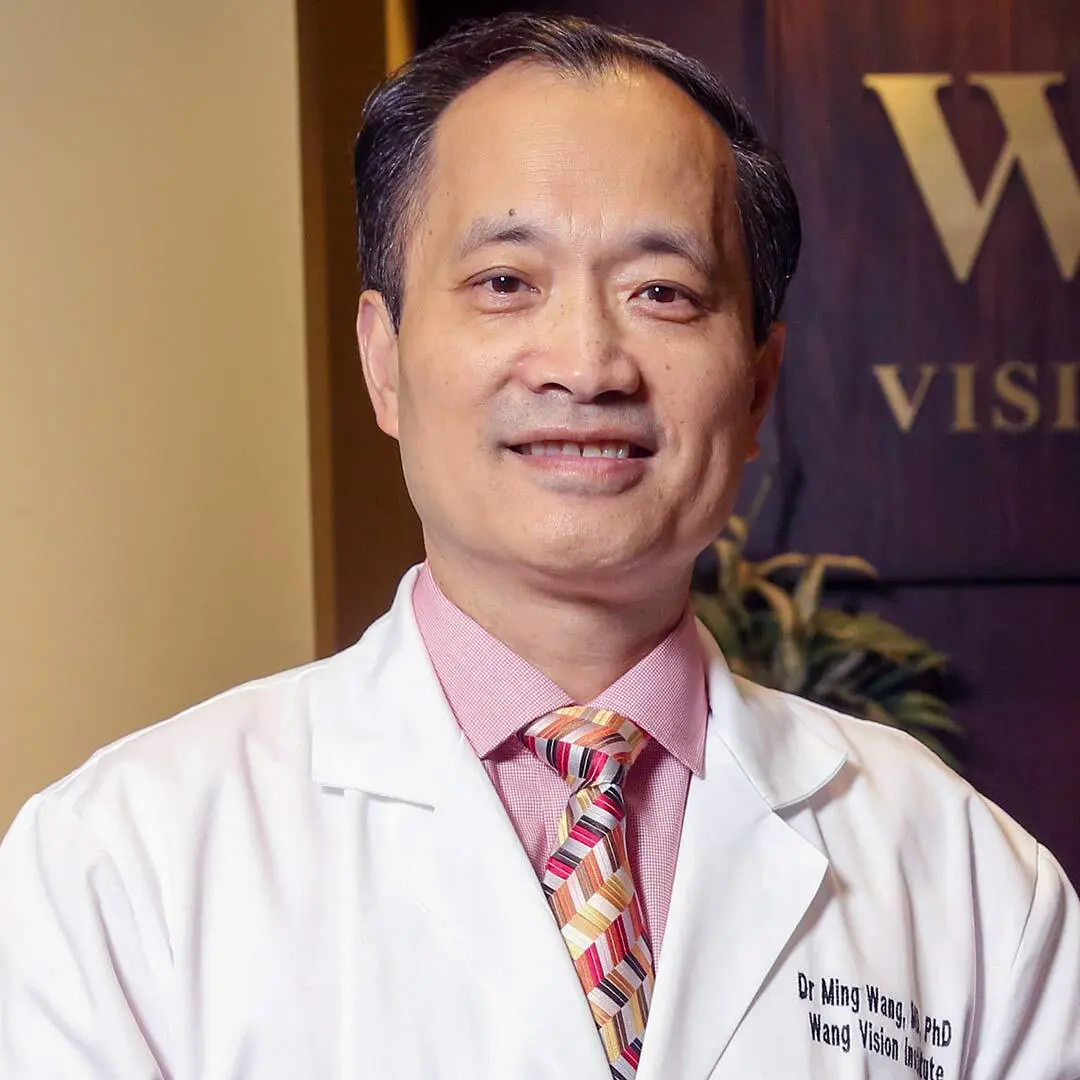

Then Communist leader Mao Zedong died in 1976, ending the draconian measures. Schools reopened in time for Wang to earn his undergraduate degree and set off for the United States, where he would go on to become an ophthalmologist known for innovations in LASIK and cataract surgeries.

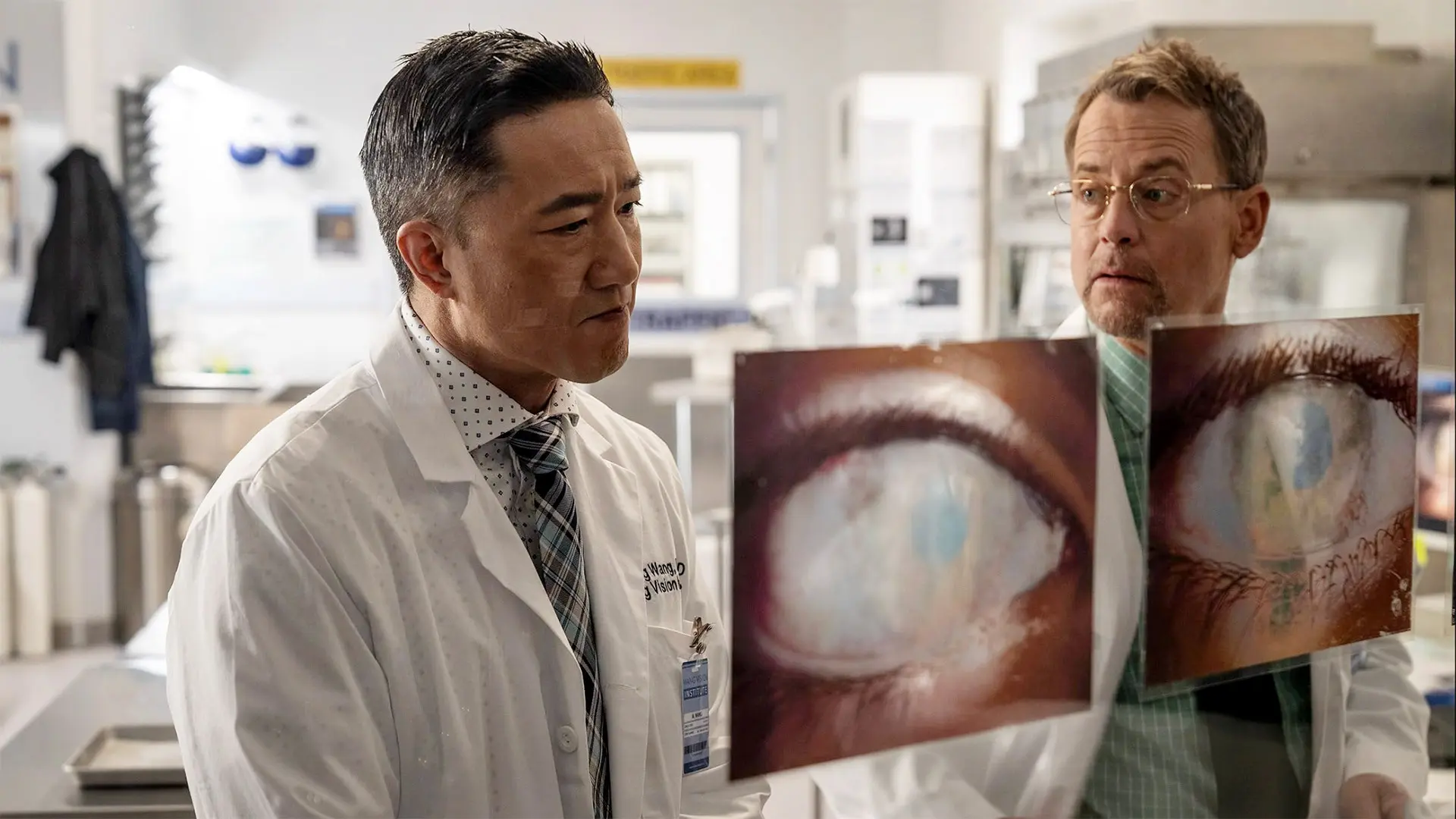

Now, his life is the subject of a movie starring Terry Chen and Greg Kinnear called “

,” out in theaters nationwide May 24. It tells the story of Wang’s treatment of a 5-year-old orphaned Indian girl, Kajal, whose stepmother had blinded her with acid, so she could earn more money begging in the streets. The movie flashes back to his childhood in China and his early days in the U.S. as he works to restore her vision. “It’s a very humbling experience,” he said of the movie, distributed by Christian-themed Angel Studios. “Other than kung fu or Chinese dynasties, I haven’t seen much about Chinese Americans, particularly first-generation Chinese immigrants.”

“It’s a very humbling experience,” he said of the movie, distributed by Christian-themed Angel Studios. “Other than kung fu or Chinese dynasties, I haven’t seen much about Chinese Americans, particularly first-generation Chinese immigrants.”

Wang was inspired to become an ophthalmologist after a friend’s father was blinded in a factory accident. While studying at the University of Science and Technology of China, he attended a lecture by University of Maryland Professor James McNesby, who encouraged Wang to come to the United States to earn his doctorate in laser spectroscopy under him.

He arrived in Washington, D.C., knowing almost no English and carrying only $50, most of which he spent on a taxi ride to College Park. He recalled soon walking across campus with two fellow Chinese students, each dressed in a three-piece suit—something his mother had spent two months of her salary on—because they wanted to be well-dressed in America. But after getting laughed at, a scene depicted in the film, they quickly went to the Salvation Army to buy clothes for a quarter in hopes of blending in.

After graduation, he earned his M.D. from a combined program of the Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and established himself in Nashville as a laser eye surgeon and researcher. Over the past three decades, he’s performed more than 55,000 laser vision corrections and published 10 textbooks.

But he also sought to make a bigger impact. After meeting Kajal in the late 1990s, he became interested in helping children like her around the world with injury-caused blindness.

“Vision is such an important sense—the loss of it is the most devastating,” he said. Wang discovered that amniotic membranes from discarded placentas had healing properties, so he developed a contact lens based on the thin membrane. It serves as both a protective bandage and promotes faster recovery, reducing scar tissue. He also established the Wang Foundation for Sight Restoration to perform free vision improvement services for children in need. “I’m answering Christ’s calling,” said Wang, a devout Christian.

“Vision is such an important sense—the loss of it is the most devastating,” he said. Wang discovered that amniotic membranes from discarded placentas had healing properties, so he developed a contact lens based on the thin membrane. It serves as both a protective bandage and promotes faster recovery, reducing scar tissue. He also established the Wang Foundation for Sight Restoration to perform free vision improvement services for children in need. “I’m answering Christ’s calling,” said Wang, a devout Christian.

Outside of ophthalmology, Wang continues to nurture his talents in the performing arts. He holds an annual Eye Ball, which raises money for transportation and lodging costs for his foundation’s patients, which combines his love of ballroom dancing with his passion for healing. He’s even played the erhu, a Chinese string instrument, on Dolly Parton’s album “Those Were the Days,” a connection he developed after she came to him for laser vision correction.

“‘Sight’ is about encouraging all of us to seeing beyond the challenges we face in life,” said Wang, who was on set during the filming of the movie. “I hope to encourage and inspire Asian American immigrants to stand up, speak up and tell our stories.”